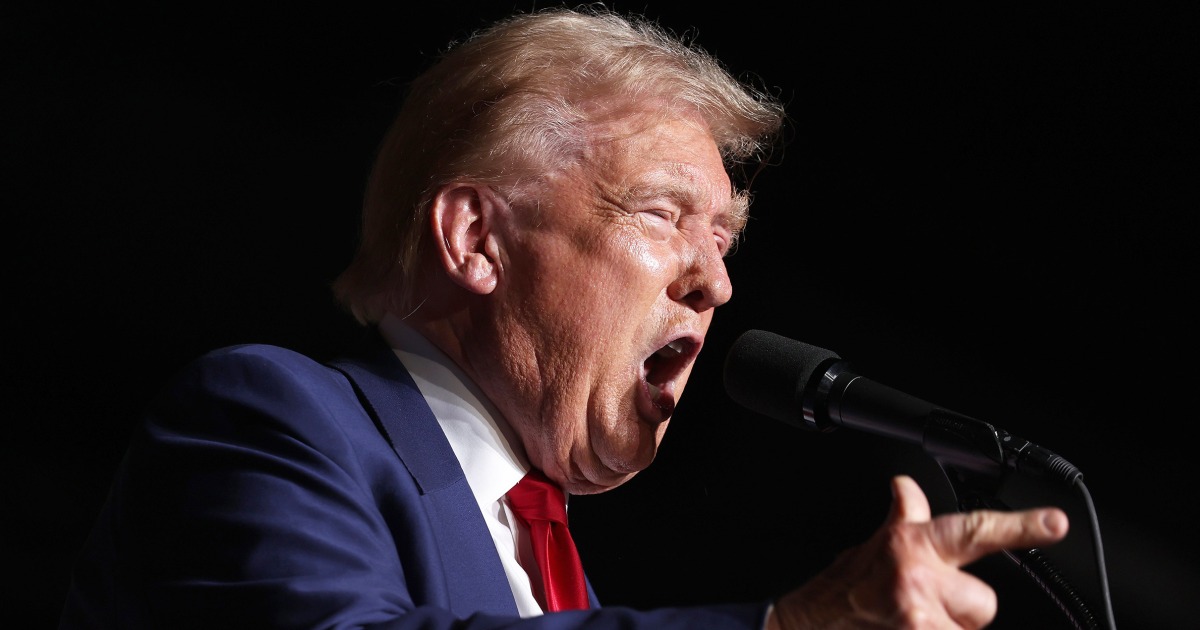

On Sunday, there was another apparent attempt on the life of former President Donald Trump. Though the suspect was never close enough to Trump to have him in rifle range and his motive is unclear, Trump said on Fox News that the man “believed the rhetoric of Biden and Harris, and he acted on it.” In a fundraising email, the Trump campaign repeated this line and illustrated it with a screenshot of a social media post from the “Kamala HQ” account that included a video of Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., calling Trump “extremely dangerous” and “a threat to democracy.”

Similarly, his running mate, Sen. JD Vance, R-Ohio, posted, “Kamala Harris has said that ‘Democracy is on the line’ in her race against President Trump” and “[t]he gunman agreed.” Numerous prominent right-wing media figures, such as Ben Shapiro, Tim Pool and Chaya Raichik (of Libs of TikTok fame) have taken up the same talking point. Shapiro, for example, blamed those who claim Trump “is Hitler without the mustache” for inspiring the suspect. And Trump himself doubled down on the point in a long X post, writing, “Because of this Communist Left Rhetoric, the bullets are flying, and it will only get worse!”

Part of my problem with the theory of ‘stochastic terrorism’ has always been that no one anywhere seems to apply it consistently.

What no one seems to notice is that, in effect, Trump, Vance and their media surrogates are echoing the claims previously made by many on the left about “stochastic terrorism” and the relationship between speech and violence.

The theory of “stochastic terrorism” holds that people who engage in overheated or irresponsible rhetoric are, in effect, inciting violence — even if they never actually advocate violence. Even though it’s “stochastic” (i.e., random, insofar as any particular act of violence can’t be predicted), it’s still supposed to count as a form of de facto “terrorism” because it increases the general likelihood of such acts’ taking place.

David Corn, for example, called Trump a “stochastic terrorist” in Mother Jones magazine. Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, D-N.Y., alleged during an appearance on “The Breakfast Club” radio show that death threats against her increased when Tucker Carlson talked about her on his show, and she said that “this is what stochastic terrorism is.”

Certainly, it’s wildly hypocritical for the right to suddenly embrace this equation of overheated speech with violence the moment it becomes convenient for it, after years of dismissing such charges out of hand. None of the figures I just listed have ever considered themselves responsible for hate crimes against trans people or immigrants, for example, despite their many years of harsh rhetoric about these groups.

A host and columnist for the conservative media empire The Blaze challenged his readers to “[t]ry to imagine a world in which Barack Obama survived two assassination attempts and the media didn’t publicly destroy the reputation of everyone who issued even the most mild criticism of the man.” In reality, while no assassin ever came close enough to fire a shot at Obama, there were numerous foiled attempts on Obama’s life comparable to the incident on Sunday. And if we’re going to play this game, it’s worth pointing out that plenty of right-wingers essentially called Obama “Hitler without the mustache” while he was president. Obama-as-Hitler signs were a common sight at early tea party rallies and protests outside town halls to discuss health care reform.

That having been said, it’s also inconsistent for many of my fellow leftists and progressives to suddenly dismiss the same ideas about speech and violence that far too many of them have themselves been eager to promote in the past.

Part of my problem with the theory of “stochastic terrorism” has always been that no one anywhere seems to apply it consistently. Those who blame the other team’s “overheated” rhetoric for political violence tend to turn around and defend equally white-hot rhetoric with which they are sympathetic and become appropriately skeptical about the cause-and-effect connections between that rhetoric and violence.

Much of the debate about whether a given piece of rhetoric is “overheated” boils down to whether the underlying facts merit the heat. For example, if Trump really is a threat to democracy, it seems absurd to say that Bernie Sanders shouldn’t say so because some people who agree with him might act on that belief in ways he himself would never condone.

Much of the debate about whether a given piece of rhetoric is ‘overheated’ boils down to whether the underlying facts merit the heat.

Or, for example, I wrote numerous articles during the life of late Secretary of State Henry Kissinger calling him a war criminal and a “monster” responsible for the deaths of vast numbers of innocent people from Vietnam and Cambodia (where he and Richard Nixon orchestrated brutal bombing campaigns) to Chile (where they backed the overthrow of democratically elected socialist president Salvador Allende). At the time I was writing these articles, Kissinger was still given fawning treatment by many mainstream media outlets. Well, if someone who’d read my articles had shot up a television studio where Kissinger was being interviewed, would I therefore have been responsible?

How you answer that question will probably boil down to whether you think my condemnation of Kissinger was correct on the merits of the case. I’ve never heard anyone say, “What you’re saying right now is completely true, but it would be stochastic terrorism to say it out loud.”

In general, the problem with focusing too much on the hypocrisy of your ideological enemies is that it can be an excuse to never have to clarify your own principles. It’s much easier to point out other people’s inconsistencies than to spell out what you yourself believe.

So here’s what I believe: I’m a democratic socialist. That means the core of my politics is about seeking to overcome the domination of society by wealthy interests. I want to empower the working class. Well, you can’t believe that ordinary working-class people are capable of governing themselves while also believing that it’s too dangerous to expose them to the “wrong” kinds of speech lest they draw conclusions with which even the speaker would disagree. As such, I care very deeply about free speech.

I’m also “conservative” enough to believe in individual moral responsibility.

If Bernie says Trump is a threat to democracy but he also frequently condemns political violence of all kinds, he isn’t therefore responsible for people who agree with him on the first part but disagree on the second. In fact, he could well argue any threat to democracy posed by Trump’s movement would be increased if he were killed, which his followers would certainly blame on a vast shadowy “them.”

And, for that matter, if right-wingers say abortion is murder but disapprove of individual citizens’ engaging in “vigilantism” against abortion doctors, I passionately disagree with the first part, but I don’t blame them for the actions of anyone who disagrees with them about the second.

In both cases, arguing about whether the position is inflammatory is mostly just a distraction from arguing about whether it’s true. If we make it easier to censor people engaging in “stochastic terrorism,” then the determination about what counts will simply be made by whichever faction happens to hold power at any given time. If you aren’t confident that your faction will eternally hold power, that should give you pause.

We’re far better off making a robust distinction between speech and violence. The more we blur that line, the harder it will be to defend robust norms about free speech. Let’s not go down that road.

Leave a Reply