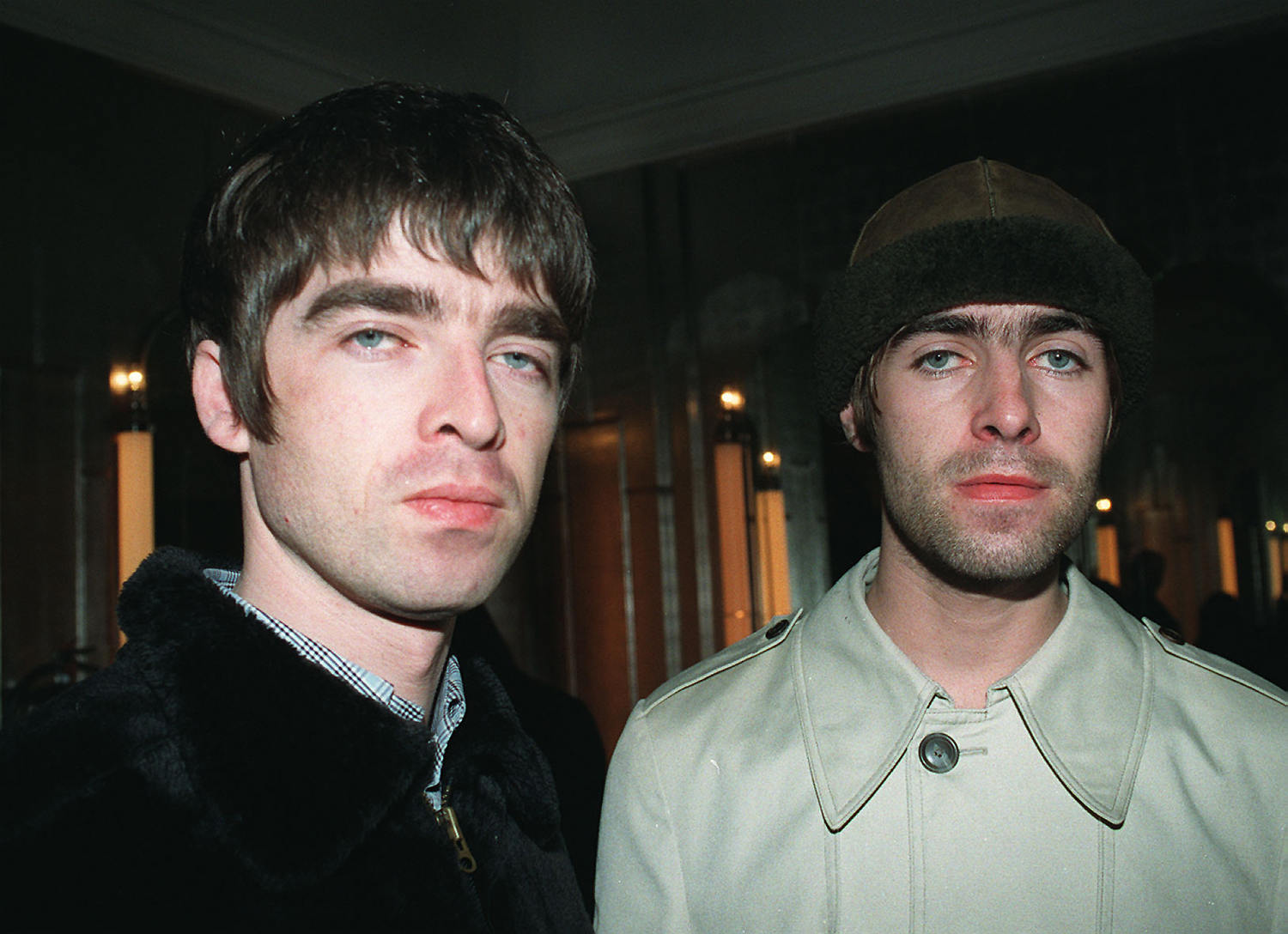

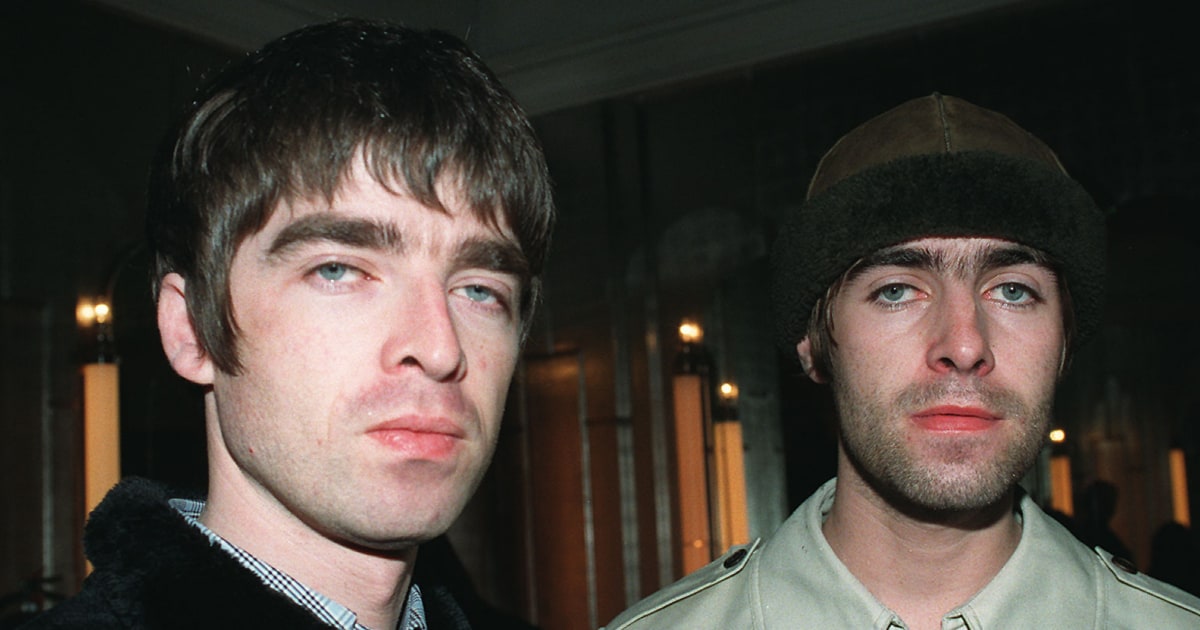

Oasis shook the music world and millions of millennials Tuesday with its announcement of a reunion tour, after a 15-year hiatus. Liam and Noel Gallagher, brothers and leaders of the band, have a famously volatile relationship, vacillating between a close brotherly bond and high-profile spats in which they publicly trade barbs. The separation started with a fight backstage in 2009. But the members of the band have decided to reunite at a time when the world is in desperate need of what Oasis has embodied since it exploded on the music scene three decades ago and defined the sound of Britpop.

The members of the band have decided to reunite at a time when the world is in desperate need of what Oasis has embodied since it exploded on the music scene.

In this digital age, which reinforces binaries, promotes reductiveness and collapses conversations, we need a band like Oasis that contains elements that are seemingly contradictory. The band is grungy and nihilistic (with songs like “Cigarettes and Alcohol”), yet hopeful (“Live Forever,” “Wonderwall”). In some ways it feels static, almost anachronistic, in the way it embodies ’90s Britpop. Picture Liam Gallagher with his hallmark stance onstage, in which he barely moves and clasps his hands behind his back. In other ways Oasis is so dynamic. Sonically, the band’s dynamism can be heard within songs (the rich layers) and between songs (from rock songs with punk bents to soft acoustic ballads). It is in its ability to contain contradictions that Oasis offers us some much-needed humanity, nuance and complexity. We are not one thing. We contain ranges, paradoxes, contradictions, multitudes. This is what it is to be human.

The embodiment of the band’s contradictions is perhaps best evinced in its expressions of masculinity and gender. In many ways, the brothers, especially Liam, represent and engender toxic masculinity: for example, getting in drunken physical altercations in their football (soccer) jerseys. Or, as noted above, getting in bravado-fueled public spats with each other and sometimes other musicians. British pop star Robbie Williams once described the Gallaghers as “gigantic bullies.” The brothers, to a certain extent, are walking tropes.

Yet there is an aching vulnerability in so many of their songs. And their vulnerability spans the personal and the existential. The personal vulnerability is exhibited in songs like “Slide Away,” from the band’s debut album, “Definitely Maybe,” which Noel wrote amid his heartbreak over ex-girlfriend Louise Jones.

Then there’s “Little James,” a sweet song Liam wrote for his then-girlfriend, Patsy Kensit, and her son, James (“Sailed out to sea, your mum you and me / You swam the ocean like a child … Thank you for your smile / You make it all worthwhile to us”). Or “Talk Tonight,” one of its epic B-sides (Oasis subverted tradition by sometimes saving some of its best songs for B-sides). It’s a tender acoustic song Noel wrote when he almost left the band after one of their infamous fights in the ’90s.

The Gallagher brothers, with their often contentious relationship, also embody forgiveness and reconciliation.

The existential vulnerability is contained in songs like “D’ You Know What I Mean?” with lyrics like: “I met my maker, I made him cry / And on my shoulder, he asked me why / His people won’t fly through the storm / I said, ‘Listen up, man. They don’t even know you’re born.’” Or there’s “Live Forever”: “Maybe I just wanna fly / Wanna live, I don’t wanna die / Maybe I just wanna breathe / Maybe I just don’t believe / Maybe you’re the same as me / We see things they’ll never see / You and I are gonna live forever.” Or “Champagne Supernova” — which, aside from the lyrics — captures both longing and surrender through its sonic dynamism, like the sound of waves gently lapping and crashing at the opening of the song or in the epic guitar solo (another hallmark feature of Oasis), which mirrors and enhances the mood of the lyrics.

The Gallagher brothers, with their often contentious relationship, also embody forgiveness and reconciliation. They seem to always return to each other — even if it takes 15 years. Such reconciliation is a practice we would be well served to remember.

It is their ability to contain such range that makes them so transcendent — or, rather, it’s what enhances the transcendence of their music. They remind us that as much as the culture is trying to push us into restricting binaries, multiple realities can be true at once.

Leave a Reply