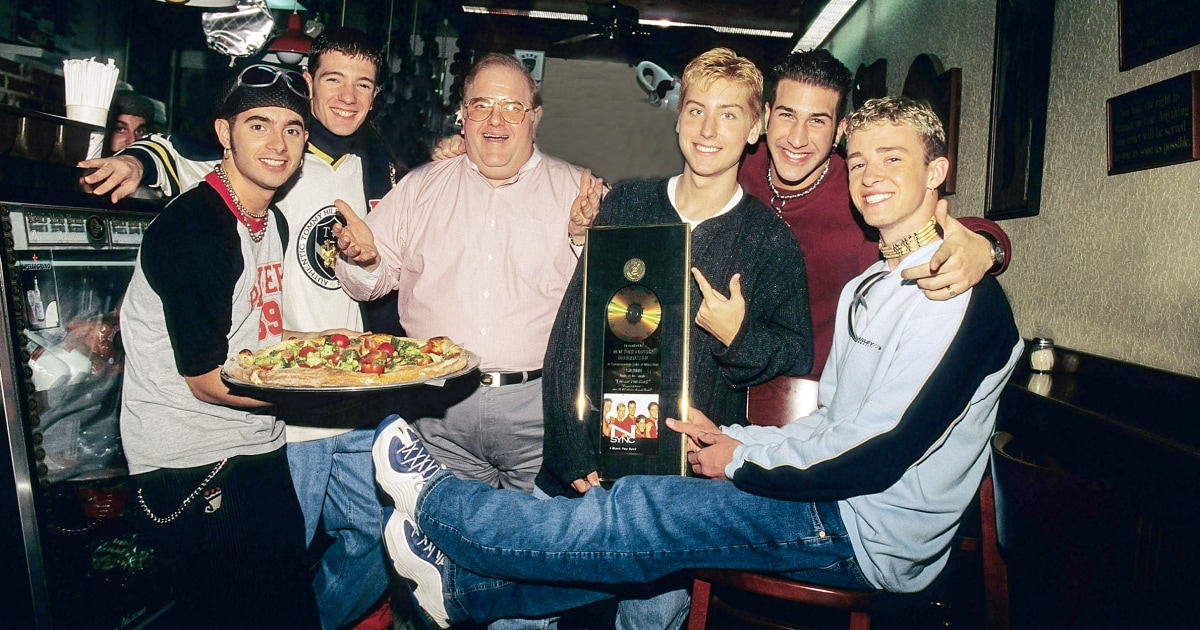

Netflix’s limited docuseries “Dirty Pop,” which debuted Wednesday, chronicles how Lou Pearlman, the man who put together the Backstreet Boys and ‘N Sync, also put together one of the biggest Ponzi schemes in history. Additionally, the Netflix series documents how the bands were started using dirty money — and how their success subsequently helped Pearlman build a house — really, an empire — of cards, through which he defrauded everyone from elderly couples investing their life savings to the Bank of America.

Pearlman, who in 2008 was sentenced to 25 years in prison for a $300 million Ponzi and bank fraud scheme, died in prison in August 2016 at age 62.

Pearlman, who in 2008 was sentenced to 25 years in prison for a $300 million Ponzi and bank fraud scheme, died in prison in August 2016 at age 62. He had pleaded guilty to federal charges of conspiracy to commit an offense against the United States, money laundering and presenting or using a false claim in a bankruptcy proceeding.

The docuseries is a compelling watch, especially for millennials like me whose glee at the never-before-seen footage of the boy bands will likely be followed by the crushing realization that we’re getting old. But it’s a very clever way into a story of financial crimes, which can run the risk of being dry and hard to follow.

“Dirty Pop” uses the rise of the Backstreet Boys and ‘N Sync — including interviews with some of its members — to tell a captivating and complicated story of how Pearlman created decadeslong careers and irrevocably shaped the zeitgeist, as he ruined lives at the same time. More than anything, it probes the underbelly of unfettered late-stage capitalism, implicitly reminding its viewers that it’s built on exploitation and preys on the most vulnerable. The docuseries paints the portrait of a man who seemed to have an uncanny talent for homing in on people who were vulnerable — and therefore ripe for exploitation — and could help him advance his fraudulence.

The absurdity of it is itself a critique of the economic system Pearlman gamed. For instance, he started a blimp rental company, but, strangely, nearly every blimp crashed. “It was almost a joke … of people talking about how all the blimps crashed,” Melissa Moylan, Pearlman’s artist representative, says. In the film, Michael Johnson, a member of Natural, yet another boy band Pearlman started, describes the crashing blimps as an “insurance scheme” and said Pearlman used the insurance proceeds to bankroll the creation of Backstreet Boys and ‘N Sync.

As for his creation of those two boy bands, Pearlman famously told a writer for The New Yorker: “My feeling was, where there’s McDonald’s, there’s Burger King, and where there’s Coke there’s Pepsi, and where there’s Backstreet Boys there’s going to be someone else. Someone’s going to have it; why not us?” So instead of letting someone else create competition for Backstreet Boys, he created ‘N Sync, his own Pepsi, himself.

He created the longest running Ponzi scheme in American history, which, according to the documentary, spanned more than 30 years.

“Lou would always have people watch us perform,” Chris Kirkpatrick of ‘N Sync says, “It was, ‘Oh, these are Lou’s friends. Gotta schmooze them up.’ I didn’t realize that they were all these investors.” And this was how the boy bands unwittingly became part of Pearlman’s game — he created the longest running Ponzi scheme in American history, which, according to the documentary, spanned more than 30 years. (That’s slightly longer than some reporting has indicated.)

The bands’ success helped Pearlman create an image of himself as a music mogul, when, in fact, the opposite was true. He had reportedly struck a bad business deal with record label BMG in a moment of desperation, to get them to sign Backstreet Boys and ‘N Sync. It was a deal that supposedly left Pearlman with hardly any money — but he made up the difference by defrauding people. Over those 30 years, he stole hundreds of millions of dollars.

And the absurdity intensifies over the course of the series. The meat of his Ponzi scheme came through an Employee Investment Savings Account, which was purportedly FDIC-insured and backed by AIG and Lloyd’s of London. He sold this under his company Trans Continental Airlines. Come to find out, he forged all the paperwork, from bank statements to FDIC documents — and that even a photo used in the brochure touting the success of Trans Continental Airlines, which featured one of its fine planes taking off, was actually a picture of a model plane being held up in front of a runway, the documentary depicts. The hand holding the model plane was cropped out.

The FBI FBI raided Pearlman’s home and offices in 2007, leading to his guilty plea and 25-year prison sentence — a length of time that was practically unheard of then for financial crimes.

The lives destroyed by Pearlman’s fraud offer their own kind of commentary on the tenuousness of capitalism. It is a system so unregulated and unfettered that it becomes a breeding ground for people like Pearlman and Bernie Madoff, ripe for exploitation. The lack of social safety nets and the desperation this creates reminds us of the extent to which capitalism strips us of our humanity. In the documentary, one retiree, whose life savings were lost after she and her husband invested $300,000 in Pearlman’s so-called Employee Investment Savings Account, tearfully looks at the camera and says that at the time that she’d rather not wake up the next day because she didn’t know where her next dollar will come from.

The lives destroyed by Pearlman’s fraud offer their own kind of commentary on the tenuousness of capitalism.

The documentary also suggests that the death of Pearlman’s longtime friend and employee Frankie Vazquez Jr., who died by suicide in 2006, was linked to the devastation Vazquez experienced when he unearthed the truth. His own mother, a former school teacher, the documentary says, had invested in Pearlman.

The end of the docuseries is devoted to creating some kind of duality — Pearlman took so much away, but also gave so much, its interviewees suggest. But, as usual, it was the most vulnerable who lost the most. And that is to say nothing of the sense of personal devastation many of those who were close to him felt after they learned Pearlman was a con artist. “And it’s only now that I can look back at that, and [see] that’s the f—ing monster … That’s the monster that was my best friend,” says a tearful Johnson.

An equally apt name for the series — and unfettered capitalism? “Quit Playing Games (With My Heart).”

Leave a Reply