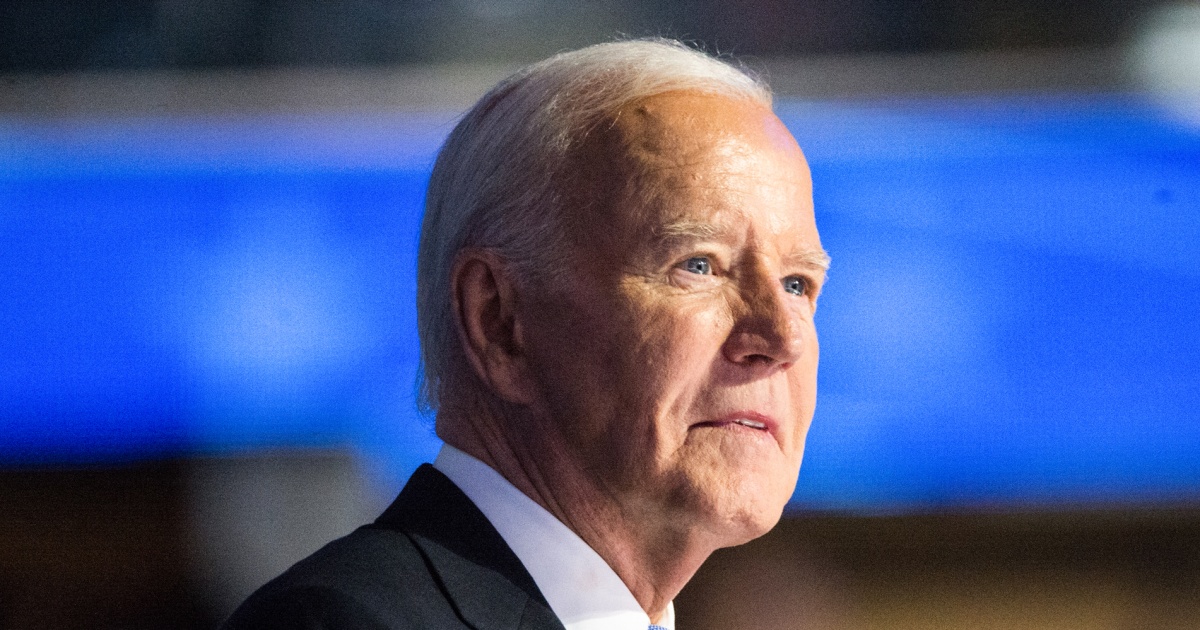

President Joe Biden commemorated the 30th anniversary of the Violence Against Women Act this week, which he introduced as a senator. As the president recognized what he called his proudest legislative achievement on Thursday, it’s worth remembering the Supreme Court’s role in curbing it.

That happened in 2000, when the justices split 5-4 in the case of United States v. Morrison. In the decision authored by then-Chief Justice William Rehnquist, the court approved striking down a provision that let gender-based violence victims sue perpetrators in federal court. The only justice from that ruling who’s still on the court today is Clarence Thomas, who joined Rehnquist’s majority opinion.

In that opinion, Rehnquist wrote that Congress lacked the authority to enact the provision. Part of the majority’s rationale for that conclusion was the Constitution’s Commerce Clause, which gives Congress the authority to regulate interstate commerce. “Gender-motivated crimes of violence are not, in any sense of the phrase, economic activity,” Rehnquist wrote.

While dissenting justices pointed to the “mountain of data assembled by Congress … showing the effects of violence against women on interstate commerce,” the majority wrote that it rejected the argument “that Congress may regulate noneconomic, violent criminal conduct based solely on that conduct’s aggregate effect on interstate commerce.”

As for other aspects of the law, Biden recounted in an op-ed in Glamour on Thursday:

With VAWA in place, we started to increase justice for survivors and accountability for perpetrators. We created the first-ever national hotline and supported shelters, rape crisis centers, housing, and legal assistance for women all across the country. We trained police officers, prosecutors, advocates, judges, and court personnel to make our justice system more fair and responsive to the needs of survivors. And, over time, we expanded access to sexual assault services on college campuses, invested in ending the backlog of rape kits, and increased protections for underserved communities.

In a section about the Biden administration addressing gun violence by domestic abusers, a White House fact sheet published in connection with the anniversary cites a more recent Supreme Court case, United States v. Rahimi, from this past term. There, the administration successfully defended a law barring gun possession for people subject to domestic violence protection orders.

But in considering Supreme Court cases on the subject, it’s important to remember a divided court’s role in cutting back the law and, more broadly in this election season in which the court is on the ballot, how the fate of landmark laws and administration initiatives comes down to the court’s composition.

Subscribe to the Deadline: Legal Newsletter for updates and expert analysis on the top legal stories. The newsletter will return to its regular weekly schedule when the Supreme Court’s next term kicks off in October.

Leave a Reply