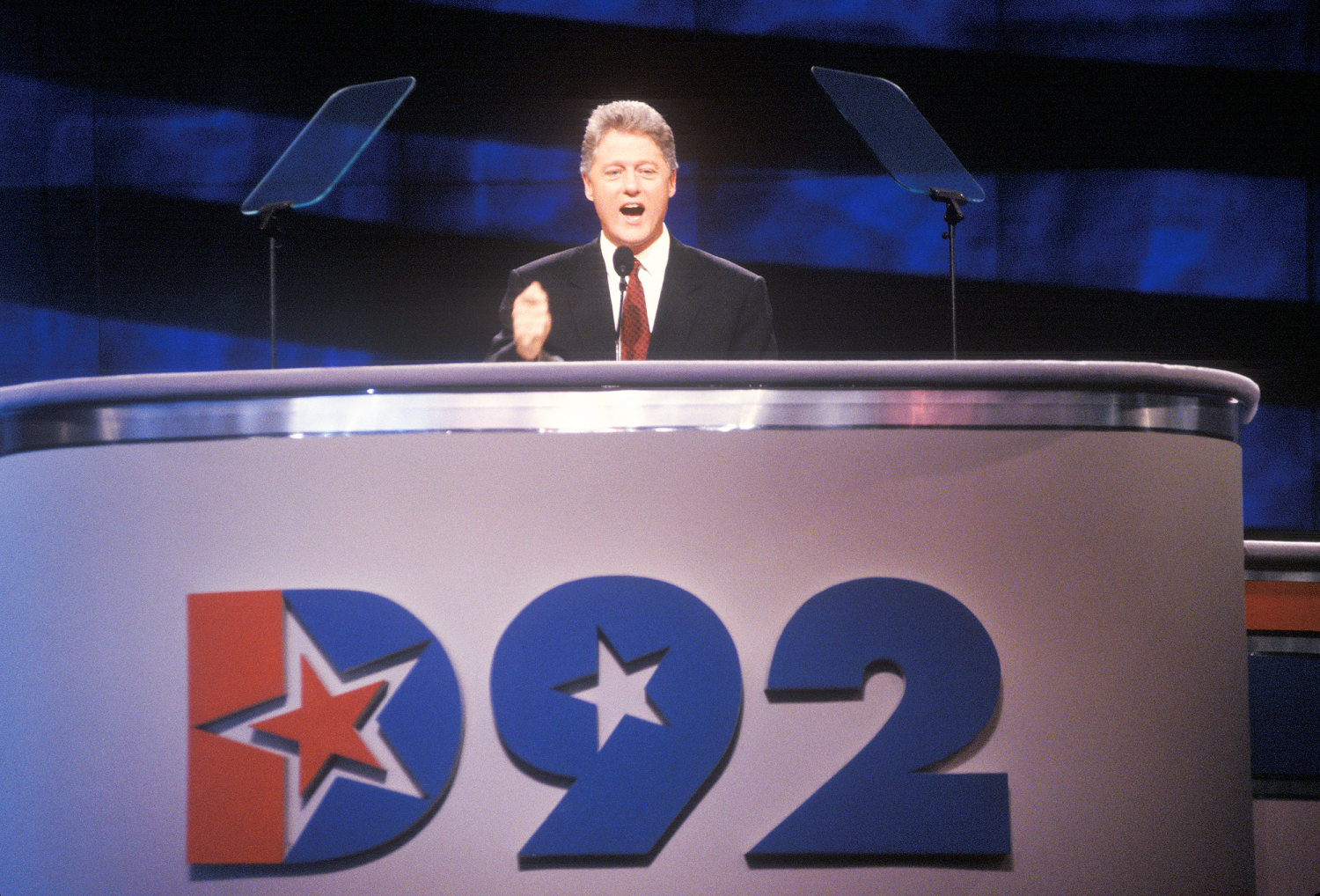

It was a different electorate when Arkansas Gov. Bill Clinton accepted his party’s nomination on behalf of the forgotten middle class in 1992.

There was no Blue Wall. Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin voted red. Democrats had lost three straight presidential elections. The electorate was 88% white, and there weren’t enough Hispanics voting to even show up in the exit polls.

“I am a product of America’s middle class. And when I am your president, you will be forgotten no more,” Clinton said to thunderous applause. He wasn’t expected to win against President George H.W. Bush, a Greatest Generation decorated veteran.

In the three decades since Clinton was first elected, enormous demographic and culture shifts have taken place.

America’s love for youth and change carried Clinton and Sen. Al Gore of Tennessee, two baby boomers from the South, to the White House. When Clinton addresses the Democratic National Convention Wednesday night, it will be with the expectation that another unlikely standard-bearer will be victorious, because Vice President Kamala Harris represents the America of today and the future just as Clinton did in his time.

In the three decades since Clinton was first elected, enormous demographic and culture shifts have taken place that dictate how campaigns are run and where they find their voters.

Still, one thing remains true: “What you stand for really matters,” says Al From, founder of the Democratic Leadership Council (DLC), which helped Clinton hone his message to win back working-class white voters, dubbed Reagan Democrats. The Rev. Jesse Jackson mocked the DLC as “Democrats for the Leisure Class” for defying liberal orthodoxy with a pro-business, trade-friendly agenda and, on cultural issues, promising to “end welfare as we know it” and put 100,000 cops on the streets, policies that addressed the anxieties of the 1980s and ’90s.

When Joe Biden won the presidency in 2020, the electorate was 20 points less white than in the Clinton era. Diverse groups are the core of the party’s support. Yet a central focus of the Harris-Walz ticket is to reach those same white voters without college degrees whom the DLC identified in 1992. Harris needs to win enough of their votes to get close to where Biden was with this group in 2020.

Clinton left office with a 66% approval rating after having created almost 23 million jobs and left a budget surplus that his successor, Bush, blew through with tax cuts for the rich. Clinton’s policies created a dream economy, but not everybody benefited, which led in part to the populist uprising we see today that is fueled by the resentments of those left behind.

“It’s hard to make judgments about the validity of policy when you’re assessing it against a reality that’s 30 years later,” From told me. “We set an agenda for the 1990s. It wasn’t an agenda for 2020.”

The ’90s were sharply partisan with Republican rabble-rouser Newt Gingrich ascending and cultural issues getting weaponized.

Trade was a big part of Clinton’s message, and it meant taking on the unions. Ross Perot, the populist billionaire from Texas, had warned during the 1992 presidential campaign that free trade would create a “giant sucking sound” as American manufacturing jobs fled across the border to Mexico. And in 1993, Perot and Vice President Al Gore held a joint TV appearance to debate the merits of NAFTA — the free-trade agreement Clinton negotiated.

Clinton championed Most Favored Nation trading access for China, comparing its historic significance to President Richard Nixon’s opening of China. The glow faded when China flooded markets with cheap exports, and if there’s one thing that Democrats and Republicans agree on today, it is the threat that China’s trade practices pose to markets and the global economy.

“It is a legitimate criticism that the people designing the Clinton program … we didn’t see how serious the impact would be on non-college workers,” says Robert Shapiro, who was Clinton’s principal economic adviser during the ’92 campaign. Trade wasn’t the only culprit. “Most of the jobs lost were not to trade but technology, but the number of workers fell sharply.”

The ’90s were sharply partisan, with Republican rabble-rouser Newt Gingrich ascending to speaker of the House and cultural issues getting more weaponized. During the 1992 campaign, Clinton had responded “yes” to a question about gays’ serving in the military. The issue took on an energy all its own and consumed much of the early months of his presidency.

Opposed were the chairman of the Joint Chiefs, Gen. Colin Powell, and Sam Nunn, the Democratic senator from Georgia who chaired the powerful Armed Services Committee. Faced with their firepower, Clinton backed down, signing compromise legislation dubbed “don’t ask, don’t tell,” which allowed gay people in the military if they followed a code of silence.

It wasn’t something Clinton was proud of, and he would compound his anger and embarrassment when, in 1996, in the middle of his re-election campaign, he reluctantly signed the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), which had passed both chambers of Congress with big bipartisan majorities. To signal his displeasure, he signed the bill alone in the White House after midnight on a Friday with no cameras present.

Clinton did what he had to as a politician navigating an intensifying conservative climate that would challenge the country. The Senate repealed “don’t ask, don’t tell” in 2010. The Supreme Court struck down DOMA in 2013 in a 5-4 ruling.

Clinton did what he had to as a politician navigating an intensifying conservative climate that would challenge the country.

The cultural issue that today’s Republicans are wielding is transgender rights. So far, Gov. Tim Walz has the best response: “Mind your own damn business.”

Clinton might have something to say about that, too. He was, after all, impeached by the Gingrich-led House. The Republican-led Senate couldn’t even muster a majority, much less the two-thirds required to convict Clinton for what most Americans viewed as a personal matter. Five Republicans joined all 45 Democrats to acquit Clinton.

Clinton carried Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin in 1992 and 1996, elevating them to the Blue Wall status they enjoy today. It was an extraordinary feat at the time, since conventional wisdom held that the GOP had a lock on the Electoral College. “We didn’t break the lock; we picked it,” Clinton strategist James Carville said at the time.

The imbalance has only grown, with the candidate who wins the popular vote not assured of prevailing in the Electoral College. Clinton and Gore harnessed the energy of their generation just as Harris and Walz (both technically baby boomers — but just barely) must inspire and motivate the generations that follow to win against these built-in structural odds.

Leave a Reply